The Art of Non-Alcoholic Spirits

blog

For decades, spirits and cocktails have fostered a culture of craft, connection, and celebration. But over time, cocktail culture has evolved far beyond the buzz!

Written by John Raiona, Executive Bourbon Steward.

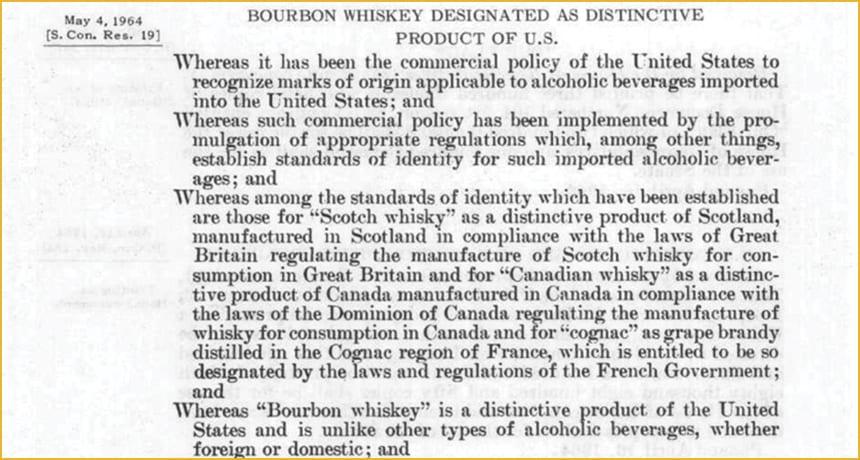

Most Bourbon Stewards might know that on May 4th, 1964, a piece of legislation declaring Bourbon "a distinctive product of the United States" surfaced in Congress. But what you might not know is this significant piece of Bourbon history is surrounded by a bit of infamy. Some lawmakers questioned giving special recognition to the humble, blue-collar drink and their reluctance was, contextually, easy to understand.

Distilling was once one of the most corrupt industries in American history. At the time, Congress had been investigating the industry for links to organized crime. The US Justice Department had targeted a group of companies known as the "Big Four" which had grown to control nearly three-quarters of the liquor trade through alleged monopolistic business practices.

In fact, the true driving force behind the 1964 resolution wasn't based on sentiment or patriotism; rather, it was the genius of an unrelenting businessman and head of Schenley Distillers Corporation — one of the world's biggest liquor companies of its time. This man's name was Lewis Rosenstiel.

Today, he is largely forgotten by an industry that has worked hard to rehabilitate its image — and who would blame them? Brands are supposed to be named after frontier icons or adorable old men you might want to adopt as your grandfather, not people like Rosenstiel, who was indicted on bootlegging charges during Prohibition and later linked to gangsters like Meyer Lansky. His rise to power included the cultivation of relationships with the likes of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and staffers under Senator Joseph McCarthy.

But even though Rosenstiel's story isn't shared as part of the approved narrative of Bourbon history, perhaps it should be. After all, he deserves much of the credit for Bourbon's 1964 recognition as America's native spirit.

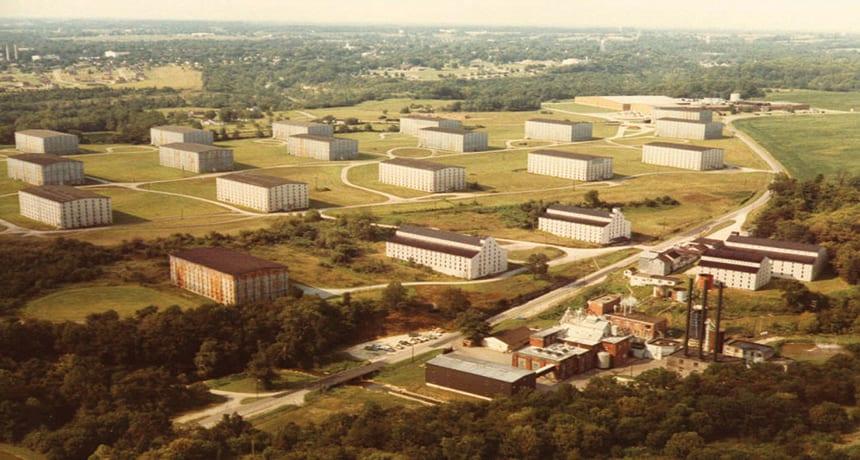

More than a decade before the establishment of Bourbon's 1964 denomination of origin, Rosenstiel had mistakenly evaluated that the Korean War would cause whiskey shortages like those America had suffered during World War II. To prepare, his distilleries ran full blast, pushing total stocks of American whiskey past 637 million gallons — enough to supply national demand for nearly eight years.

After the war ended without the shortages he had anticipated, this surplus gave him control of roughly two-thirds of all the nation's older whiskey stocks, according to his competitors (the accounting is fuzzy, but this probably referred to all whiskey older than five years).

This was a disaster from a business perspective, prompting The New York Times to run the headline, "Whiskey Industry Facing a Crisis," because even though Americans were drinking plenty of whiskey, demand was dwarfed by supply.

Federal law at the time required distillers to pay taxes on whiskey aged for eight years, at which point it had to be sold or destroyed. So if Rosenstiel were forced to sell to a market with weak demand to meet that deadline, he might have to do so at a loss, causing others to slash prices to compete and shuttering a large portion of the industry in the fallout.

Realizing the precarity of the situation, Rosenstiel looked for help from his counterparts in other companies within the Distilled Spirits Institute (DSI) — the industry's main lobbying group. He wanted tax changes that would allow him to age his whiskey longer, giving him more time to sell his surplus.

Such a rule change would have been good for the entire industry, but the other liquor chieftains balked at the advantage this would give him over their younger products. As a result, they tried to block Rosenstiel's next move: positioning his older Bourbon as a luxury good in order to capitalize on markets created by a booming post-war economy.

Sidney Frank, Schenley's vice president and Rosenstiel's son-in-law, had told reporters about the strategy and now other DSI members wanted temporary provisions preventing Rosenstiel from advertising his older products until they had the chance to catch up.

As other liquor titans attempted to undo their competitor, Rosenstiel would prove to be a challenging opponent. He quickly outflanked his DSI adversaries by forming an alternative lobbying group, the Bourbon Institute. Much later in 1973, DSI, the Bourbon Institute, and another trade group would merge to form the Distilled Spirits Council of the US (DISCUS) — the industry's main lobbying arm today.

Working swiftly, the Bourbon Institute successfully lobbied for passage of the 1958 Forand Act, which made whiskey taxes due at 20 years instead of eight, buying Rosenstiel precious time. In the long run, it would also give distillers more flexibility to create some of today's most noteworthy brands although the competitive advantage it gave to Schenley, underwritten by the government, temporarily stoked "the fury of the three other big distilling companies," as reported by The Economist.

With the Forand Act in place, Rosenstiel looked for other ways to sell his Bourbon surplus. Overseas markets beckoned, and the Bourbon Institute began its work on the resolution to declare Bourbon a "distinctive product of the United States," thereby protecting it from foreign competition; indeed, one of the resolution's opponents was a New York politician representing two Manhattan heiresses earning royalties from "Bourbon" imported from a Mexican distillery.

As the Bourbon Institute laid its groundwork, Rosenstiel poured $35 million into a global advertising campaign and sent promotional cases of Bourbon to US embassies around the world. Meanwhile, his competitors in the other three big distilling companies were burdened by their own surpluses and waning domestic demand, so they too chose to follow his lead.

On May 4th, 1964 Rosentiel got his wish. The resolution passed successfully, forever changing the industry and the world — and of course, it paid off for him as well. By the time Rosenstiel retired several years later, he had become one of the richest men in the country.

Following his death in 1976, his obituary in The New York Times declared him, "the most powerful figure in the distilled spirits industry," but couldn't resist also remembering him as "a domineering man with a quick temper." Today, he remains a significant, albeit intriguing, figure in Bourbon history. And through Bourbon, his story lives on.

Written by John Raiona, Executive Bourbon Steward.

blog

For decades, spirits and cocktails have fostered a culture of craft, connection, and celebration. But over time, cocktail culture has evolved far beyond the buzz!

blog

Those that are familiar with the process of crafting distilled spirits may also be familiar with the 10 common congeners that are created during fermentation, and honed during the distillation run. Each congener has its own distinct personality, rendering unique tastes and aromas to the finished spirit.

blog

So, you want to start distilling with freshly milled grain. Maybe you're tired of paying top dollar for the pre-milled stuff from the malt distributor, and you're ready to invest in the quality, efficiency, and bulk pricing that comes with milling your own whole grain. But where do you start?